A WALK IN THE PARK

A Kinesthetic Theory of the Arts of Landscape

For encouragement in my pursuit of answers to this question I have many to thank. My gratitude reaches all the way back to my high school Physics teacher at The Bronx High School of Science, Abraham Baumel, who was so praiseful of a term paper on “Psychophysics.” The Graduate Faculty in Philosophy at Columbia University lured me away from Philosophy of Science, and introduced me to philosophical Aesthetics, in particular, to the work of John Dewey whose insights into aesthetics have enriched my life ever since. Professor John Furlong at Harvard’s Landscape Institute shared my admiration for the work of Rudolf Arnheim and encouraged me to explore as well the works of Appleton, Pallasmaa and others; Professor John Beardsley at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design brought countless other writers to my attention and urged me to continue writing about landscape from a philosophical point of view. The support and encouragement I received as a master’s student at The Inchbald School of Design, The University of Wales, stiffened my resolve to pursue this subject as a doctoral dissertation.

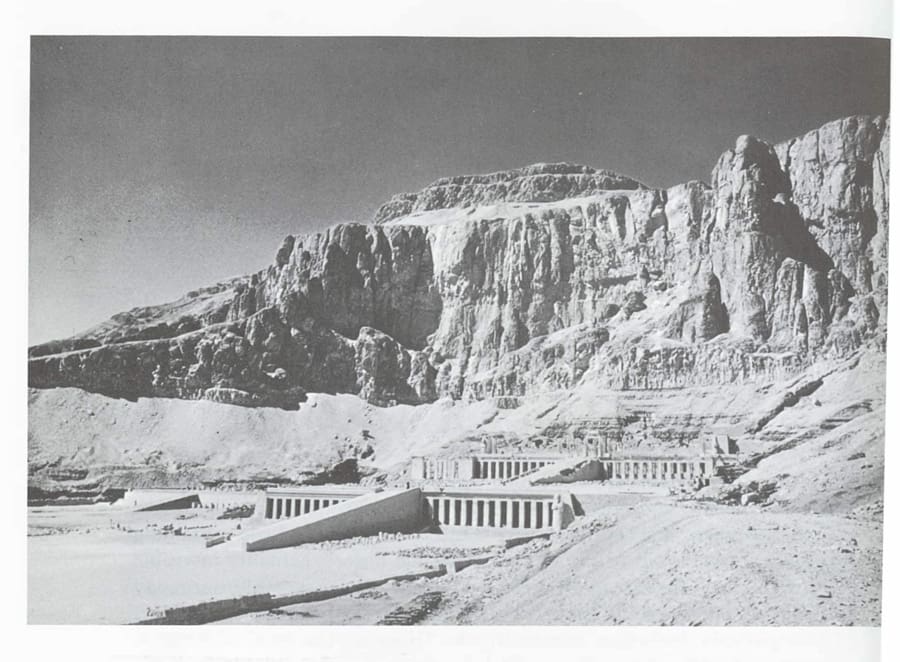

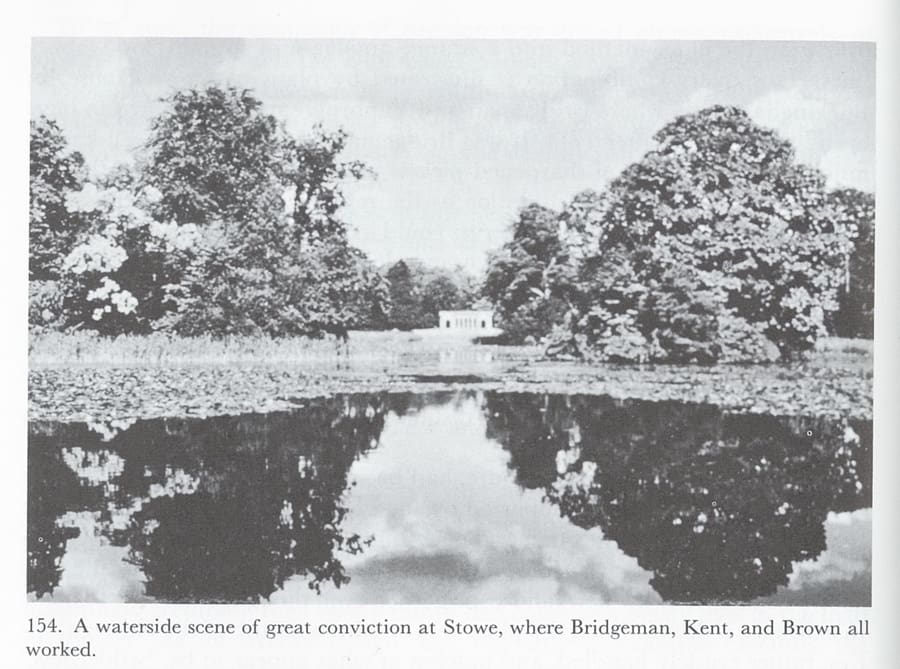

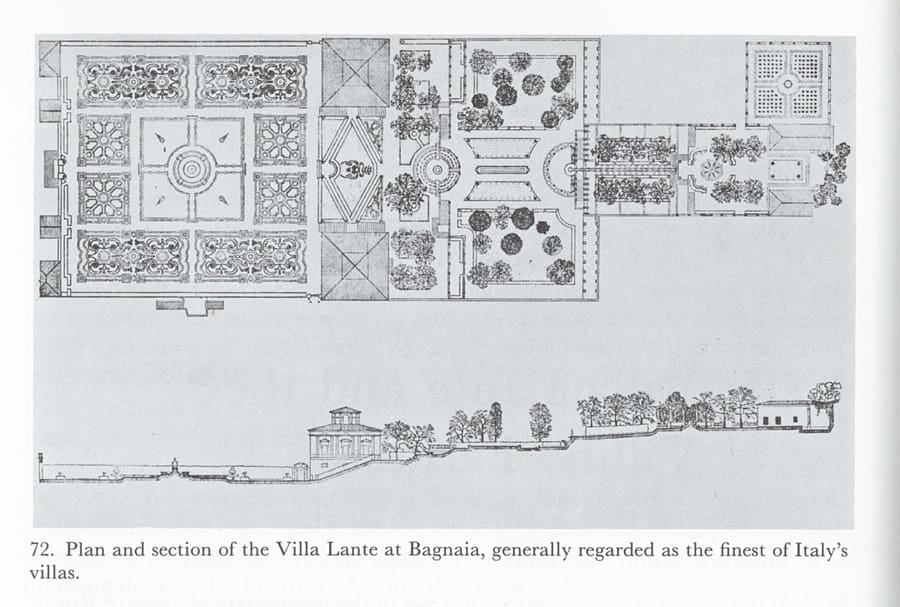

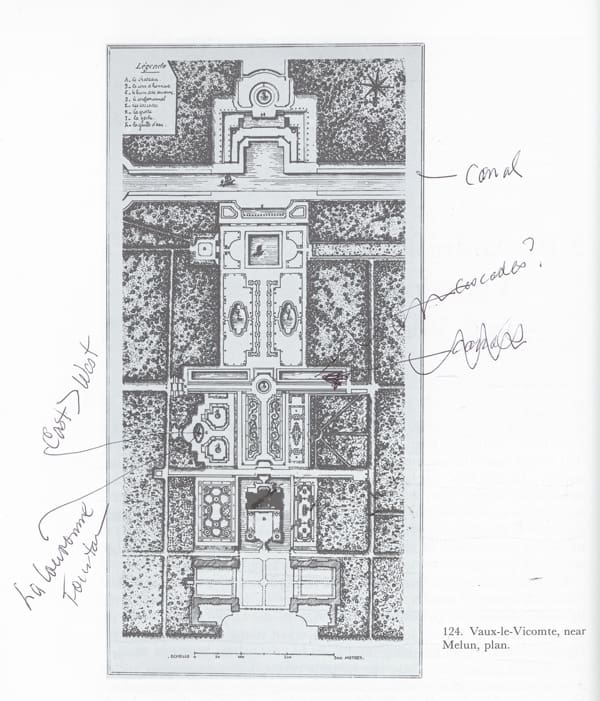

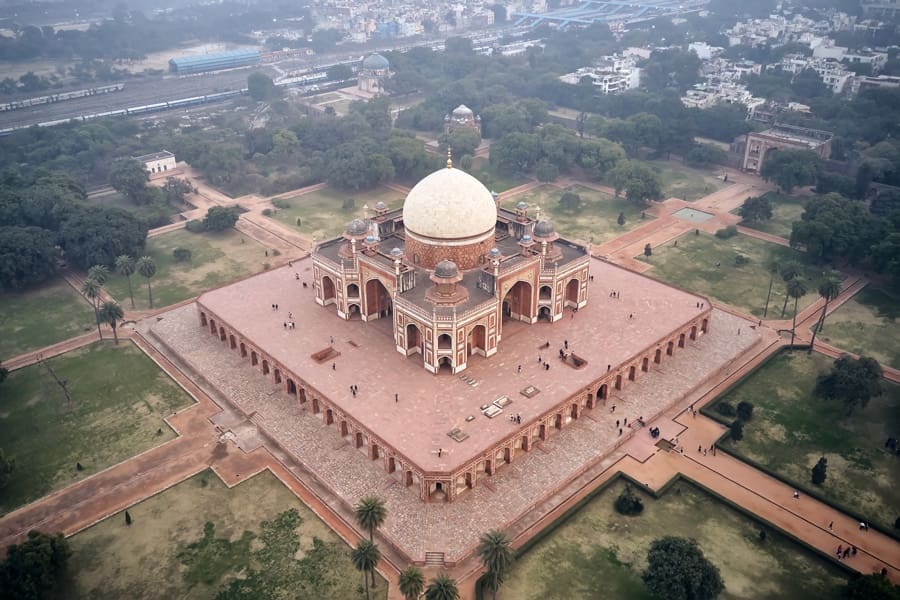

A selection of illustrative images from the book

Finally, to my husband, Jack, and to whatever unearthly beneficence made it possible for a seventy year-old woman to complete a doctoral dissertation in a subject she had long and deeply loved, and to the further blessing that allowed me, eight years later, to rewrite that dissertation as a book, I say, “thank you.”